Rob McConaghy is an engineer’s engineer. He solves mechanical and electrical engineering problems, designs and scratch-builds solutions, and is always ready to recognize the experience and contributions of his colleagues. And Rob’s longstanding project – some may say obsession – with Stirling Cycle engines is testament to his dogged pursuit of optimal solutions.

Low noise, zero emission

He’s also remarkably patient with those who are fascinated by this work, yet totally unfamiliar with the technology. An engine that appears to need no fuel. Just hot air. When you see it run, you can’t help thinking it’s kind of magical. “Well, it kind of is!”, Rob says with a smile.

He explains that Stirling engines alternately heat and cool air to create expansion and contraction that drives one or more pistons. It’s a closed system with no intake or exhaust and runs very quietly – it’s sometimes referred to as a silent engine. The air inside the engine may or may not be under pressure. The principle was invented by Rob’s namesake Robert Stirling in 1816, and subsequently developed by the Philips company as part of the war effort. These are the first engines that could genuinely be called ‘zero emission’.

A mower, a young man, and the start of a mission

The May 1964 edition of Popular Science featured a Stirling-powered lawn mower, and sparked highschooler Rob’s interest. He would go on to design and build the first of many of his own Stirling engines as he pursued a degree in Mechanical Engineering – the early stages of what was to become a career-long preoccupation. Fast-forward to June 24th, 1987 when Rob, his family and friends visit 60 Acres Park in Kirkland for the maiden flight of his scratch-built plane, powered by a scratch-built Stirling engine of his own design.

1987: world’s first Stirling-powered airplane

It was a unique experiment: the first airplane ever to be powered by hot air. Not so unusual – certainly for RC plane enthusiasts – was the result. The first few flights ended in crashes, “Not because of engineering problems,” Rob’s quick to point out. “Entirely down to pilot error.” But after a few more flights, the required piloting skills developed and the model rose to 50 or 60 feet, to fly for 15 minutes. “There’s something special,” says Rob, “About seeing the engine actually fly an airplane. To me, it was deeply satisfying.”

The engine produced some 20 watts of power, which Rob says is about the minimum required to support a plane. The air inside the cylinders can be at current atmospheric pressure, but in this case, it was initially pressurized using a bicycle pump; increased pressure in these engines provides for increased power at the expense of slightly less smooth operation. Propane brought the heat, and air passing across exposed coils circling the body of the engine acted as the coolant.

Research, development, and publication

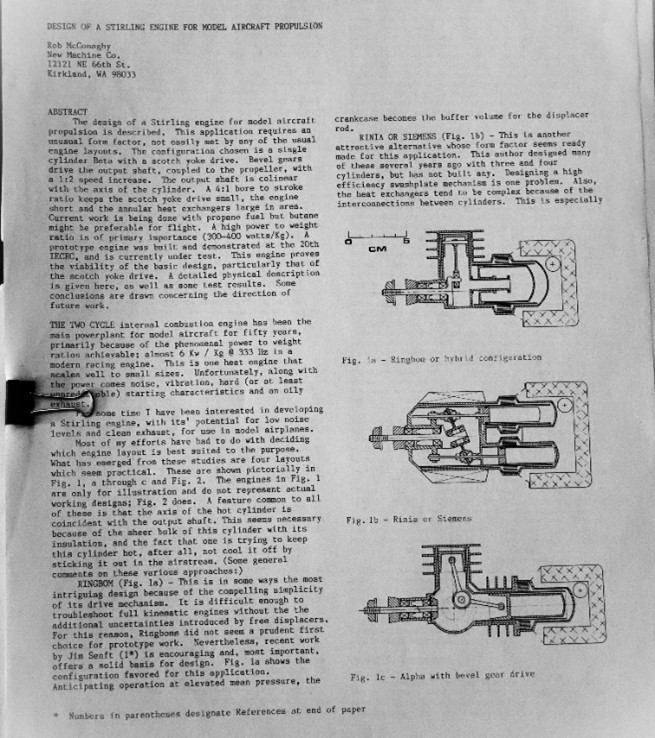

Since that time, Rob has continued to experiment with different designs, materials, and alternative gases to plain hot air. Prestigious publications such as the IEEE Energy Conversion Engineering Conference, and Model Engineer magazine have published the results of Rob’s work as he has continued to evaluate, build, and refine. In one such article Rob says, “I can’t tell you how much time I have spent pondering the ideal engine layout for use in a model.” At that time, he also predicted the eventual ubiquity of electric motors. Like his Stirling engines, they represented a “..quiet, clean, easy to start power plant.” And Rob correctly predicted that people would eventually be prepared to pay the price in added weight for that convenience.

In common with the fundamental principle of his engines, Rob says the development and progress of related energy conversion technologies seems also to be cyclic in nature. The pursuit of diverse designs for energy conversion has led to the proliferation of options we have today, but some technologies – such as steam, solar, and even hot air – persist, returning in evolved forms to drive new solutions. Steam engines return as nuclear-powered steam turbines, and the oldest source of energy, the sun, can now be harnessed to power a huge variety of devices including trains, planes, automobiles – and even space stations.

From the Northwest to NASA

And, just to prove there is nothing new under that sun, NASA announced in March 2020 a Stirling Cycle engine at its Glenn Research Center that has been running continuously and without any maintenance now for over 14 years.

Today, Rob maintains his interest in Stirling Cycle technology, though recognizes how broadly his electric motor predictions in the ‘80s have, in fact, materialized.

“My son has a Tesla,” he says. “Though I haven’t driven it.” After speaking with him for a while about his work you realize that, among all the impressive features of his son’s Tesla, perhaps the least interesting for Rob would be the driving part.

Flight video

George Washington noted that, “Perseverance and spirit have done wonders in all ages.” Click here for home video of Rob’s perseverance at 60 Acres.

Click here if you’re impatient enough to jump straight to his record-making successful flight.

Select references

McConaghy (January and February 1996), “A Hot Aero Engine”, parts 1 and 2, Model Engineer magazine

McConaghy (1986), “Design of a Stirling Engine for Model Aircraft Propulsion”. IECEC: 490–493

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons; Popular Science archive; Rob McConaghy. Photography, video transfer: Chris Randall. Text: Richard Machin